In this post, I reprise something, somewhat edited, that I wrote on my blog Like Mother, Like Daughter. It concerns the insights of the last chapter of Romano Guardini’s The Spirit of the Liturgy, the book that inspired one of the same name by then-Cardinal Ratzinger. Although one may have some issues with Guardini, his thoughts in this excellent work are, overall, important for understanding what the liturgy is.

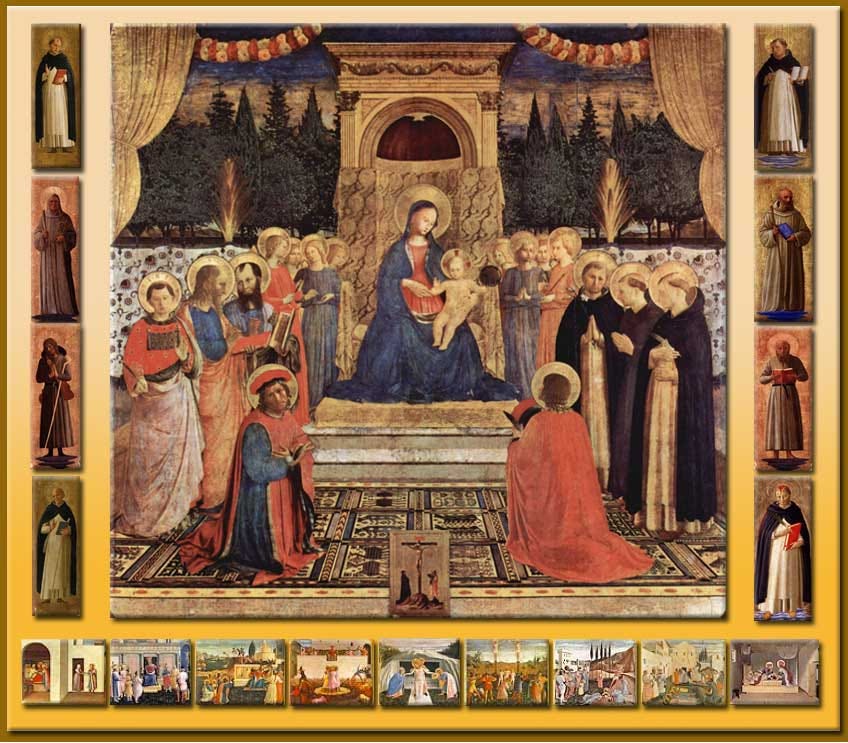

Fra Angelico: San Marco Altarpiece

The distinction between Logos and Ethos contains the key of how to approach the “active participation” idea underlying the post-Vatican II Church — an idea that dominates and deforms our worship.

The last chapter of Guardini’s The Spirit of the Liturgy, entitled The Primacy of the Logos over the Ethos, and its fundamental distinction between being and doing, offers the definitive organizing principle for evaluating the claims of those defending the Novus Ordo against a return to Tradition.

Internalizing this distinction between Logos and Ethos gives us the clarity to order life correctly, bestowing meaning on things we moderns may find obscure— things like the traditional forms of Christian worship (eastern and western) and the idea of contemplation. In general, it helps us realize that some things are givens, which means “things to be received.” And these things cannot be forced to be something they are not by an effort of will.

Guardini helps us understand the ability of the Church to refine each temperament to be like that of Christ’s. She infuses Christ’s stillness in the active man and gives Christ’s energy to the sedate man. With her universality, she warns us from the error of making the Liturgy in our own image.

You see, in the course of history, there came to be a divide that fell between man and that which is beyond man. We can often feel that philosophy has nothing to do with our everyday lives, yet this is not true. What we think about things really matters. And in the West, many centuries ago, the very greatest thinkers began to doubt that there is a connection between the material world and the immaterial world; they doubted that the immaterial world is even real; most importantly, they doubted that words have a meaning connected to what they are — that they are not simply random things we have agreed on to get on.

Doubt fell on man. Doubt that he could ever see the truth… doubt that truth exists apart from what he sees in front of him. And, of course, this led to doubt about God and His existence. (This doubt in turn led to the most fatal negation of all on earth: the erasure of meaning about the integrity of the human person, male and female.)

It’s hard for us to know we are held captive by doubt, what to do about this doubt, or how to approach doubt once we identify it. In some ways, of course, we need it; when we are testing theories about things in a scientific way; and indeed it’s the impetus behind the incredible burgeoning of scientific knowledge.

But even science (and especially science) must have something behind it — some fundamental anti-doubt — some affirmation of things as good and connected to truth and rightly ordered to truth — or else it devolves to mere laboratory work. Really aware scientists have testified to the characteristic of receptivity, of intuition, as necessary for their work to take place at all.

Receptivity is the antithesis of doubt.

Guardini speaks right away in this chapter about the restlessness of the person of action. This is a recurring theme of his, and here he goes to the root.

People [who are generously endowed with moral energy and earnestness] regret one thing in the liturgy, that its moral system has few direct relations with everyday life.

Today, now that the “moral,” as a category, has subsided, relativism having truly gained the upper hand, I think we need to substitute the term “good will,” or “benign intentions.” And for “moral system,” I think we need to substitute “plan of action.”

It’s simply the case that the ensuing time has neutered morality (the system of identifying good and evil), so that we don’t speak of it any more. Yet the type remains: the person who wants everyone to do something about what they have learned in their religion; who wants worship itself to be more dynamic.

I’d say that in this new century, this personality has gone beyond mere exhortation, establishing of movements, and urging of devotions — we now have a full-fledged, entrenched, and all-pervading bureaucracy of programmers — that is, purveyors of programs.

As Guardini states and repeats in a footnote, devotions are good and necessary, and the life of faith needs them. It’s primacy we’re looking into here.

It’s the rare parish that doesn’t consider itself first and foremost a provider of programming for the faith. The style now is to cease even calling it a church at all, but rather community or center. That which Guardini touches upon here has become a thorough-going way of life, and like its political counterpart, has its own means of reproduction. Bureaucracies, once established, are notoriously difficult to reform or remove. There is, after all, always another program to administer and another person whose livelihood depends upon doing so. And the more active and sentimental (emotions-based) a person is, the greater their influence when left unchecked.

It’s hard to step back from all the activity and ask some questions, for two reasons. I’ll get to the second towards the end of this discussion. The first is that we’re all rationalists now. We are all doubters in that Cartesian sense.

The rationalist uses analysis, taking things apart, as a substitute for seeing things whole (in Latin, ratio, discursive reasoning, vs. intellectus, the part of the intellect that sees and receives knowledge effortlessly) — that is, we are all inheritors of this legacy of falling back on activity and will; of living according to Ethos as the highest principle.

I’d say that most of us do have a secret suspicion that we’re better off doing a program about faith than going to Mass; we feel more fulfilled by a lively Bible study than by praying Vespers, should we ever get the chance — or we’d like our liturgy and prayer to be a Bible study. And it’s the “new order” Church that has taught us this.

We are convinced that the best remedy for poor preparation for marriage is another, better program for marriage preparation. When we think of religion, we think of catechesis. When we think of passing along the faith to our children, we think of religious education classes.

It’s not that studying the faith or preparing for marriage with a class are bad things. Not at all. They can be good things. Yet…

One person asked me, when I was describing this new model of the church, and deploring the making of Sunday into another day of busy-ness, of learning and teaching and classes and programs, “Well, what would the church be? Would there just be… the sacraments?”

Reader, I hardly knew what to say. I could only manage a quiet yes.

Josef Pieper, in his book on Happiness and Contemplation, reminds us that the political life, according to Aristotle, exists for something beyond itself: for what is not political.

In fact, and this might shock us a little, as again, we are rationalists to some extent, political life is not even for some ideal life of the common good here on earth. No, we take part in the political life to secure peace, that we might have breathing space in order to devote ourselves to contemplation of the good.

Totalitarians, Pieper tells us, will allow “spare time [recreation]. But not true repose.”

Dr. Johnson said, “To be happy at home is the ultimate result of all ambition.” And what is the home? The home is where all work is ordered to the day of worship, that we might contemplate the Good.

The home is the least efficient place, which is why those social engineers and busybodies who are always trying to better things attack the home first. If you are aiming at running things more smoothly, something like dormitories and collective nurseries work much better. No, the home, like the Church of which it is a little exemplar, exists for its own sake — allowing the person freedom to come in contact with God. But I digress.

Guardini:

This predominance of the will [Ethos] and of the idea of its value gives the present day its peculiar character. It is the reason for its restless pressing forward, the stringent limiting of its hours of labor, the precipitancy of its enjoyment; hence, too, the worship of success, of strength, of action; hence the striving after power, and generally the exaggerated opinion of the value of time, and the compulsion to exhaust oneself by activity till the end.

The Church, he says, can speak to us in any age, “but it must be pointed out that an extensive, biased, and lasting predominance of the will over knowledge is profoundly at variance with the Catholic spirit.”

If not:

Religion becomes increasingly turned towards the world, and cheerfully secular. It develops more and more into a consecration of temporal human existence in its various aspects, into a sanctification of earthly activity, of vocational labor, of communal and family life, and so on.

In short, a kind of club.

While life’s center of gravity was shifting from the Logos to the Ethos [during this revolution in thought I was telling you about], life itself was growing increasingly unrestrained. Man’s will was required to be responsible for him.

Man seeks to become God, because only God’s will can ultimately take responsibility.

This presumption is guilty of having put modern man into the position of a blind person groping his way in the dark, because the fundamental force upon which it has based life — the will — is blind. The will can function and produce, but cannot see. From this is derived the restlessness which nowhere finds tranquillity. Nothing is left, nothing stands firm, everything alters, life is in continual flux; it is a constant struggle, search, and wandering.

Catholicism opposes this attitude with all its strength.

This is strong, is it not? All these good things: doing, acting, working for the good, seeking to take responsibility — if they are made primary, then the faith must resist them.

The Church forgives everything more readily than an attack on truth. She knows that if a man falls, but leaves truth unimpaired, he will find his way back again. But if he attacks the vital principle, then the sacred order of life is demolished. Moreover, the Church has constantly viewed with the deepest distrust every ethical conception of truth and of dogma.

This discussion is about the order of good things. Truth and dogma are for themselves. They don’t exist for a purpose, they don’t exist to make us better or to make a good place to live on earth, although devotion to them may have those effects.

This “ethical conception” — turning everything into a force for the will, including the truth itself! — is not how the Church ultimately does things. Guardini rightly states, “Truth is not obliged to give an account of itself.”

And what is Logos, then? In the quote above, Guardini mentions that the will can function but cannot see. Logos, the Greek word for Word, relates to man’s faculty of the intellect which sees things whole, all at once: contemplation. Logos is seeing the Good.

Seeing has to do with man’s highest faculty, the intellect; whereas doing relates to the will. The perennial argument, much more intensified in our age, is which of these principles has primacy? Guardini, following Aristotle and Aquinas, is trying to show us that the answer is not the will.

The Logos, of course, is Jesus Christ, the Word of God. Pieper (a student of Guardini) uses the wonderful image of thirst to explain how contemplation is our fulfillment here on earth. He explains that when we thirst, we long for something. And when we drink, we receive that thing — we receive it as a gift, in fact. From Happiness and Contemplation:

A man drinks… and feeling refreshment permeating his body… says, “What a glorious thing is fresh water!” Such a man… has already taken a step toward that “seeing of the beloved object” which is contemplation…

Think of Jesus by the well, telling the woman that He is the living water. We thirst, and our seeking (so important!) is the will, moving us to the good. But when we are quenched, that is no longer an act of the will. It’s its opposite: the receiving of the gift.

What is our contact with this Logos, now that Jesus is not walking on the earth?

It’s Sunday. It’s worship. It’s the Mass. It’s the Liturgy.

Guardini:

The soul needs that spiritual relaxation in which the convulsions of the will are stilled, the restlessness of struggle quietened, and the shrieking of desire silenced; and that is fundamentally and primarily the act of intention by which thought perceives truth, and the spirit is silent before its splendid majesty.

In the liturgy the Logos has been assigned its fitting precedence over the will.

I said, above, that there are two reasons we find it hard to step back from all the activity, the striving, to take a look at what we are doing to worship.

The first reason was that we are rationalists willy-nilly, just by living in this age. The second is that for the majority of people, the worship we are offered does not have this character of the stilling of restlessness, of repose, of receptivity to the beauty of truth.

Worship itself has been invaded by the spirit of Ethos, of “active participation.” My intention here is simply to observe this, not to rehash all the reasons this is so, as I strongly believe that the rehash is amply achieved elsewhere. No, I want us to get at the root of what the effect of this invasion is, to think about it, to feel it in our bones the way we stop and take stock of the health of our own body.

At some point we have to step back from “I thirst!” and wonder why we have such a hard time finding a drink of fresh, clear, living water. Where is this water?

I’d venture to say that for most of us, worship is not what it ought to be, and it’s not usually in our control to change that; simply because when we try, we are met with the charge of opposing active participation — in short, with a failure of Ethos.

On the contrary. We must return to the Church’s treasury of Logos — of her eternal form of worship.

The liturgy has something in itself reminiscent of the stars, of their eternally fixed and even course, of their inflexible order, of their profound silence, and of the infinite space in which they are poised. It is only in appearance, however, that the liturgy is so detached and untroubled by the actions and strivings and moral position of men. For in reality it knows that those who live by it will be true and spiritually sound, and at peace to the depths of their being; and that when they leave its sacred confines to enter life they will be men of courage.

Don’t wish to take out a paid subscription just now? I understand!

How about this:

Great article, thanks! I think that one of the reasons that it's hard to find repose and peace in the Novus Ordo is that there are so many "roles" to fill in the mass, from "bringing up the gifts" to being a lector, "extraordinary minister," etc. that for those who are of this busy-activity type of personality, it can be unsettling not to be "participating." Whereas in the TLM, on the other hand, there is no expectation of anything other than prayer and repose.

An incredibly perceptive essay. Thank you so much.