… Though it’s unclear what the point really is, say what you will about collegiality and so on in the Spirit of Vatican II. If that were the point, it seems to me it goes directly against the other Spirit of Vatican II, full participation of the laity, since concelebration says “us, not you” in a fairly obvious way, though no one ever mentions it, perhaps out of politeness.

Sometimes all the theological reasons for or against something can be greatly clarified by just looking at that thing.

Concelebration is an example.

Is it what it purports to be? When we experience it, whether as priests, if we be priests, or as members of the congregation, what do we really think?

All of us felt sick when we heard the news of the fire at the Notre Dame Cathedral. We all endured the paroxysms of anguish when the brainstorming about what to do began. We all breathed in relief when the intention was formed to rebuild exactly as it was.

I’m sure I’m not alone in watching the various documentaries about its restoration. You probably were just as delighted to discover the existence of craftsmen willing and able to provide ancient oaks for the structure of the roof and tower. There is so much to rejoice in at its rebirth.

All the old things are good and fitting.

The new, though… in the new, things are not in keeping with the old.

Leave aside the meaningful vestments — meaningful in what way is a topic for another post. (One clergyman kept his wits about him, I see, at least as regards his liturgical garb.)

Just look.

The occasion of the re-opening of Notre Dame Cathedral is a good example in the concelebration discussion, in part because undoubtedly, having one priest celebrate Mass at its high altar in the good old-fashioned way, would demonstrate everything that the New Mass purports to remedy. Or would it?

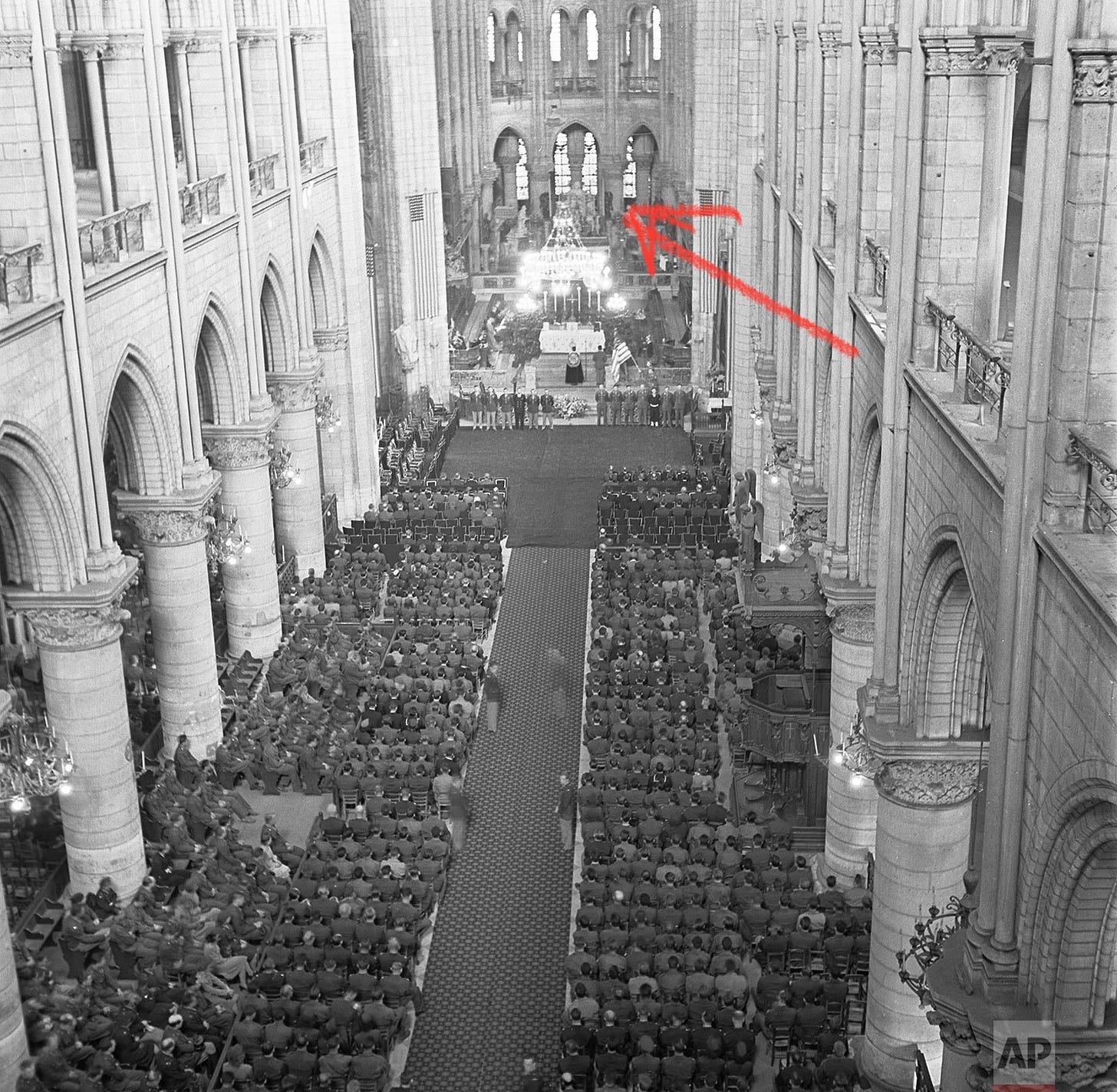

I’ve been to Notre Dame — maybe you have too. Remember how far away the high altar is? The red arrow in the image below points to it — it’s waaay beyond the chandelier and altar that catch the eye.

U.S. soldiers fill the pews of Notre Dame Cathedral, Paris, France, April 16, 1945, during the GI memorial service for U.S. President Roosevelt. (AP Photo/Morse)

In the early 20th century, that central altar was placed. It’s much nicer and more fitting than the one damaged in the fire or the new one. You can see the priest celebrating ad orientem in the photo. Even so, if you’re one of those soldiers in the back, you are bound to think yourself rather remote. It’s true.

But what do we see?

That lone priest is doing something there… something that involves an action beyond the people, beyond even himself. We can see that much.

Let’s consider another image — but keep in mind as you look that the modern camera lens considerably foreshortens our view:

Again, put aside the jarringly ugly altar.

Let me ask you — what is that one priest on the left there, the one furthest away… doing?

What does his presence signify? If, as this glorious structure emphasizes, every little thing is chosen to convey some eternal truth, what eternal truth do we apprehend by a gaggle of priests clustered around a relatively small object?

I can’t help wondering: How far away from the altar would that priest have to be for his participation to be moot, or for us to wonder, again, if we’re in the back, what he’s accomplishing?

In a slightly different context, that of “social distancing” during lockdown, Fr. Paul Mankowski offered a satirical formula to nail down the answer:

OK, well let's suppose the paten on the main corporal is 14 inches directly in front of the celebrant, and the ciborium on the adjacent corporal is the same distance from the edge of the altar but at an angle of 42 degrees from the celebrant.

The relevant trig function is sin θ = a/h, i.e. 1.4945 = h/14, whence h = 20.923.

Assuming that consecratory power is inversely proportional to the distance between priest and consecranda, this means that the hosts in the ciborium are 66.9% the Body of Christ, and that ought to be enough for any docile Catholic.

Can we really say that surrounding the altar with priests has made the sign of consecration more real to the person in the congregation, hearing Mass that day, than if had he been there in 1945 and experienced it offered by one priest, facing away from him?

Remember, a sacrament is a sign that accomplishes what it signifies. We can’t really separate the two parts of that definition. It’s not, in fact, magic, and a mere desire to do the thing isn’t enough to make it so.

If the goal of this choice is more sense of participation for the laity, does a huddle, an exclusionary posture of many, rather than just one, clergyman convey that sense?

I wrote about how it may do just the opposite — impose a strikingly clerical expression — in this article about a reason modern Catholics insist on self-communicating in the hand. Yes, I know all the theological and historical reasons. I’m speaking here of what the man in the pew sees.

Really look: What is the symbolism of this (a rare photo of concelebrating priests before Vatican II):

Their vestments are undeniably beautiful, so there’s that (and no attempt at spurious uniformity was made!). A little less than half of them are celebrating ad orientem. But then, the others are closing the circle.

No access point for the Returning Lord, symbolically speaking (the Lord will come again, though). Which one of them represents Christ — which one is alter Christus for this action? Do we believe on a visceral level that they can all represent Him at the same time, at one Mass?

It seems to me we don’t come away with the vision of the High Priest offering Himself to the Father in a holy sacrifice of the altar.

Tradition-minded people have good arguments for why concelebration as innovated in the Mass of Paul VI doesn’t correspond to any real liturgical value. But it may be just as fruitful to pay attention to what really goes on when it happens, whether in our parishes or at Notre Dame.

What do you think when you see it?

Not ready to subscribe, but enjoyed this post? How about this:

![r/Catholicism - [Free Friday] The Second Vatican Council Fathers offer the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass in 1966. A rare combination: ad-orientem and concelebrating at a freestanding altar. r/Catholicism - [Free Friday] The Second Vatican Council Fathers offer the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass in 1966. A rare combination: ad-orientem and concelebrating at a freestanding altar.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F2c0fc9e2-e3e4-407e-be7f-bfb4ca12d541_640x476.jpeg)

It's remarkable that you put this out just after I was celebrating private Mass. During Mass, I was hit with thoughts of how the hatred of Private Mass (including it being banned at St. Peter's Basilica) is so destructive of priestly identity.

How many people does it take to screw in a lightbulb? Just one, but everyone benefits from the light. How many priests does it take to offer the holy sacrifice of the mass? Just one, and everyone present still benefits from it!